Scroll Down for Other 2017 Shortlist books

“Dick’s out of town,” she says. “He’s at another fub.”

My wife has her own way

of describing my book events.

Fub –

short for Finger Up Butt.

I’ve sure done my share

of standing around, ignored. Book

signings in empty stores, roundtables as the least popular panelist, and

readings before an open bar.

Awkward ? Yes. But not “ahhh-ch-ward.”

Awkward ? Yes. But not “ahhh-ch-ward.”

At least I could say I have

never had to perform parrot sex in front of my parents.

On the eve of his 2017 Leacock

Medal win, Gary Barwin entertained his mom, dad, and others chewing on poultry at

Orillia’s Mariposa Inn with an animated reading from Yiddish

for Pirates. The chosen excerpts told

of piracy and persecution, love and lashings, the Torah and torrid parrot sex.

I know no one who doesn’t

laugh at the book’s premise: a pirate story told by a five-hundred-year-old kibitzing

African grey from a perch in a Florida seniors’ residence. With a sip from the

fountain of youth and hundreds of years to learn, the narrator, Aaron, absorbed

many languages, many stories, and enough Yiddish to give life to his reminisces

of high seas adventure on the shoulder of his master Moishe. Moishe, or, when

opportune, Miguel, was a Lithuanian Jew whose life leads him through

Inquisition-era Spain to the captain’s chair of a Caribbean pirate ship.

I like to laugh, read

engaging stories, and even to listen to old timers parroting their memories. I

enjoyed the book in this way. But I can’t

help reading stuff like Yiddish for

Pirates through the lens of the Leacock Medal and my aspirations to be a writer

with fewer fubs.

Obviously, the premise creates a powerful vessel that is easy to recognize as something different. But it could have run off into a sea of clichés and corniness in my hands.

Gary Barwin avoids

the reefs with skill and imagination worth studying. A composer, poet, and artist as well as

author of twenty books, he executes the parrot and pirate idea with great creativity,

and this might be expected. But he also brings in his affection for Yiddish

culture and his knowledge of history in an elegant way that informs and

inspires without ever pushing the story off course or taking the wind out of

its sails by saying stuff like “avoid the reefs,” “off course,” and “taking the

wind out its sails” – too much.

Gary Barwin avoids

the reefs with skill and imagination worth studying. A composer, poet, and artist as well as

author of twenty books, he executes the parrot and pirate idea with great creativity,

and this might be expected. But he also brings in his affection for Yiddish

culture and his knowledge of history in an elegant way that informs and

inspires without ever pushing the story off course or taking the wind out of

its sails by saying stuff like “avoid the reefs,” “off course,” and “taking the

wind out its sails” – too much.

With the same mastery, Barwin uses the

Spanish Inquisition, piracy, and people of another era to raise touchy issues of

today and suggest why the persecuted might find recourse in terrorizing

violence. A parrot seeking a partner

after months at sea, oblivious to the willingness, gender, and precise sub-species

of the other also speaks to the interface of casual sex, loneliness, biology, and

the mores of other animals.

Some book reviewers laud

Barwin for a “postmodern” style and his “deconstruction” of the novel. I think reviewers just like to say “postmodern”

and “deconstruction” when they can. It

is particularly impressive if you can do it twice in one paragraph.

But I see Yiddish for Pirates as an homage to classic novels. Aaron certainly reminds me of the narrator of

Don Quixote, a translator of a second-hand

account written in Arabic; and much in Moishe’s story (the book’s full title is

Yiddish

for Pirates: Being an Account of Moishe the Captain, His Meshugeneh Life and

Astounding Adventures, His Sarah, the Horizon, Books and Treasure, as Told by

Aaron, His African Grey) echoes Gulliver’s

Travels (originally Travels into

Several Remote Nations of the World. In Four Parts by Lemuel Gulliver, First a

Surgeon, and then a Captain of Several Ships). The book also sits well beside earlier

Leacock Medal works like Morley Torgov’s that introduced others to Jewish

community and cares with humour and kibitzing stories.

|

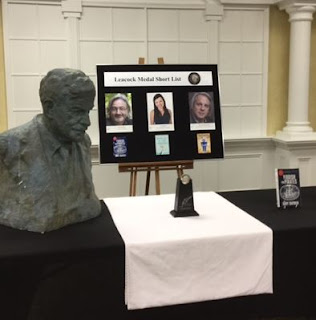

| Leacock looking down as Gary performs Parrot Sex |

It hooks you and reflects the force of Yiddish for Pirates, which all flies out of that funny premise and the parrot narrator. We don’t expect perfect grammar. Whole sentences. Words that we should

recognize. Or even word-like sounds. We accept candor and cover-ups equally. It sets the stage for unconstrained and bold

story telling.

So my lesson here is that when feathered,

you can be unfettered – and be more entertaining in book writing and book readings.

I will think about this a lot when I

try to write future fiction, and maybe, I should buy a parrot costume and

practice thrusting motions for my next fub.

Writing Exercise

Recount a 17th century expedition

up the Ottawa River through the mouth of a voyageur’s edgy pet beaver Fub - throw in some aboriginal science fiction. (Here is my shot at it).