by Ernest Buckler

LESSON

31

The appeal of silly

A 2013 Ottawa Valley “Bad Poetry Contest” drew hundreds of entries and overwhelmed the organizers, who were challenged in evaluating all the good bad poetry. It seems more people like the art form than regularly admit it. We stay in the shadows until something like this contest allows us to indulge in the fancy without critique.

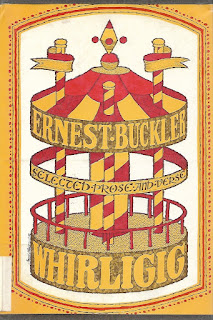

I suspect Ernest

Buckler might have been pursuing this same awkward pastime when he wrote the

essays, poems, and stories bound into Whirligig, the 1978 Leacock Medal

winner. At the time, Canadians knew Buckler best as the novelist whose first

work, The Mountain and the Valley, sat in the highest rankings of serious

Canadian fiction.

Some of the essays in Whirligig are clever and generally consistent with his thoughtful persona. They include an account of early social networking (the Rural Party Line) and an examination of the Christmas card tradition that demands a process for ensuring cards are never sent to the undeserving and are never too fulsome in their messages.

These essays could, and

often did, stand on their own as witty magazine or journal articles.

But I find the book

more interesting when Buckler plays with different formats and takes shots at

his own profession.

Unlike Farley Mowat, Pierre Berton, and other writers who adapted well to the rise of television and mass media in the 1970s, Buckler was uncomfortable with self-promotion and bookselling based on the personality of the writer. A recluse who stuck close to his rural Nova Scotia home, he had a hard time with the pressure to produce a “roguish thumbnail sketch” and photo of “excruciating cuteness” for a writer “otherwise as sober as oatmeal.”

In the chapter

“Bestsellers Make Strange Bedfellows,” Buckler deconstructs the process of book

sales, marketing, and promotion with the insight of someone who worked as a

book reviewer as well as an author. Aspiring writers with full-time employment,

families,

In the chapter

“Bestsellers Make Strange Bedfellows,” Buckler deconstructs the process of book

sales, marketing, and promotion with the insight of someone who worked as a

book reviewer as well as an author. Aspiring writers with full-time employment,

families,

and other demands might

be heartened by Buckler’s piece on being a writer while also farming, with its

inescapable demands tied to the seasons and living creatures. These bits of

prose are fun.

Yet Whirligig is

memorable because of the parts when the serious Buckler lets loose in quirky,

sometimes bad, poetry . . . bawdy limericks, works of many stanzas, and poems

of two lines; poems about animals, religion, culture, relationships, marriage,

and — often — sex.

It’s hard to believe that the bookish Buckler, a lifelong bachelor, was not releasing more than a pent-up imagination in “Withdrawal Symptoms or Slam, Bam, Thank You Ma’am/I Trust You Wore Your Diaphragm” or the “Matinee Idle,” which muses about live sex on stage and the strain of eight shows per week: “But where is the actor — With enough vital factor.”

His poems like “Never

Laugh at a Giraffe” with its ode to “the elephant who wears no trunks,” “the

porcupine [that] sports crochet hooks,” and other beasts could evoke the

animal-based poetry of Sarah Binks. But it’s not exactly the same.

I have difficulty defining good or bad poetry. But I know Sarah’s poems were amusing because they were framed by an admiring biography. Buckler’s poems and essays don’t have this feature. They can be rhythmic, emotive, and scholarly, but also irregular and disconnected.

The one-time University of Toronto president Claude Bissell said, in the book’s intro, that the pieces in Whirligig were “written at various times” and this makes the sum “an occasional book,” which is another way of saying “a bathroom reader” — a format that might not have propelled Buckler into the upper strata of Canadian literati, but is still, like good-bad poetry, something many of us enjoy when behind closed doors.

WRITING EXERCISE

Write

your own author profile for a publisher’s website in a way that shows you did

it begrudgingly and with contempt.

Buckler Bits

- Ernest

Redmond Buckler, born in 1908, earned a B.A. degree at Dalhousie University followed

by an M.A. at the University of Toronto in 1931. After university, he worked as

an actuary in the “penitentiary” of the Toronto offices of Manufacturer’s Life.

- Then

in 1936, he returned to his family farm in Nova Scotia’s Annapolis Valley. In

1938, at the age of thirty, Buckler won a modest magazine article contest,

which was enough to encourage him into a writing career.

- But

he stayed on the farm until he passed away in 1984.

- The

Mountain and the Valley, published in 1952, is

consistently ranked among the best novels in Canadian literature. A follow-up, The

Cruelest Month, fell short of the commercial and critical achievement of

his first. In addition to these and Whirligig, his other books include his 1968

memoir, Oxbells and Fireflies. He wrote text for Nova Scotia: Window

on the Sea, published in 1973.

- As a reviewer, he wrote for Esquire, Saturday Night, the New York Times, and the Los Angeles Times.