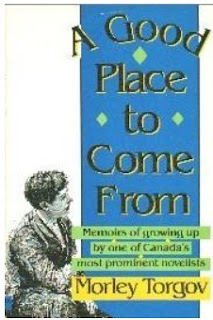

1975 Leacock Medal winner

A Good Place to Come From

by Morley Torgov

Click Here for Audio of Podcast

This podcast episode is

about the 1975 Leacock Medal winner, A Good Place to Come From by Morley

Torgov. It is a collection of stories that flow from the author's days growing

up in the 1930s and 40s within the small Jewish community in Sault Ste. Marie,

Ontario. Morley Torgov who lives in Toronto will celebrate his 95th birthday in

2022.

DBD

Thanks so much for

doing this. And it's no small honour to be able to talk to you.

Morley

Torgov (MT)

Oh you’re welcome.

Thank you.

DBD

I guess you must have

been in your 40s when you wrote A Good Place to Come From?

MT

It was published when I

was 47. I started writing it, let me see, my father died in 1965. And his death

sort of liberated me to some extent, to use a lot of the material from my

childhood and my teen years, and so on and so forth.

And I started writing A

Good Place to Come From probably a year or two after he died and it was

submitted about 1973 in an unfinished form and rejected by a number of

publishers. But by the time I had enough in 1974, Beverly Slopen, my literary

agent was able to convince Lester and Orpen to publish it. And it sort of took

off. What helped a lot was a terrific

review by William French in The Globe and Mail. And from there on, it

really did quite well.

DBD

So your father passed away in 1965. That was going to be one of my questions.

The book has two sides to it. One is it's been

celebrated as a window on Jewish life in the small Canadian community where you

were growing up, this being Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario that we're talking about.

But I couldn't tell whether the prompt for the book was more desire to

celebrate your dad, or maybe just have him as a vehicle for talking about these

other things?

MT

Well, there's a bit of

both. The book is dedicated to him. Dedication reads to him “in lieu of

candles.” And he's a certainly a major force in my life, and a major character

in the book. But it's not just confined to him alone, of course, because there

was a rather rich, gold mine, I guess you'd call it of characters in the Soo

Jewish community, not all of them lovable. But all of them very interesting. So

I had a lot of material available to me.

DBD

The book is a collection of short stories.

Were any published independent prior to the book's publication?

MT

Yes. One or two of them

were published in a little magazine called Viewpoints, which was

published by a couple in Montreal. And they bought the first two pieces that I

wrote way back around 1971. And those two pieces got a fair amount of attention

at the time in the Viewpoints Magazine. And I also sold one short little

piece to the Globe and Mail weekend magazine, which was published, I

guess, about 1973. And the Editor of The Globe said, “Why don't you

publish some more of these stories?” and a couple of other people said the

same. And then the next thing I knew, I was working on a book.

DBD

Was Making of the

President 1944, one of those short stories there were published prior to

the book?

MT

No. That that was fresh

material.

DBD

It's the one (story) that seems to stick in a lot of people's minds as capturing

the dynamism of the community. As an

outsider, you know, sort of peering into this portal on the Jewish community, I

found the book engaging, but it was because of those universal themes of parent

and child relationships.

MT

That's one of the

things that I think surprised me most. That was how universal the book struck

people because I received quite a number of letters from people who were not

Jewish even, and who said that they found the themes in the book, very

universal. As you say, parent-child relationships, racial relationships,

economic problems, and so on and so forth. The book turned out in some people's

views to be much more universal than I thought it was going to be.

DBD

I was wondering as a

writer whether you were conscious of that tension between trying to speak to

the universal but give enough description of the community. It seemed to ebb

and flow in a really elegant way. I remember one thing that I appreciated was

the detail that you went into to describe the venerated role that those two New

York Yiddish newspapers Forward and The Day had in your home

because I wouldn't have appreciated the references to careers in medicine that

your father made unless they had that preamble. So yeah, it was both universal

and in enlightening or instructive to people.

MT

Well, those two

newspapers were what kept a lot of Jewish people alive in small towns, because

they were the connection between living in out of the way places like Sault

Ste. Marie and knowing what's doing in

the rest of the world. Those two newspapers, and frankly, a couple of non-Jewish

publications were very much part of our lives in Sault Ste. Marie: one was Life

magazine, which was a relatively new magazine back in those days. And now

there was Time magazine; they were the things that connected us to the

world. We didn't have television, of course. There were movies, but the movies

really weren't the kind of thing to learn the news from. But given the two most

popular Jewish newspapers from New York, plus magazines like Time and

Life, that's what sort of made us aware that there was another world out

there.

DBD

When I first read the book, I wasn't too sure what you thought of the Soo, but

I'm pretty sure now that you have affection for the place?

MT

Well, I have a great

deal of affection for the Soo. And frankly, I wouldn't be what I am or who I am

whatever that is, without having been born in the Soo and without having spent

my childhood and my teen years in the Soo. So I owe the Soo a great deal. But

I'd really be a hypocrite if I denied the fact that I couldn't wait to get out.

Because there was a great big world out there. And I knew what I wanted to do.

I couldn't do it in Sault St. Marie. In

those days, it was a city of about 25,000. It was really at the end of the

railway line literally. And classical music, for instance, was something you

got about once a week, maybe twice if you were lucky. And there was this

constant itch that I had to get out into the bigger world. So yes, I owe this Soo

a lot. But I'd be a liar if I said I would want to spend the rest of my life

there as the Soo was in those days. Today, of course, the Soo has a much larger

population and is a much more sophisticated city, but not in my time.

DBD

I was thinking as you were saying that, that your book - and maybe it probably

it wasn't intended directly, but it is sort of an homage to the culture of

Northern Ontario. There's a phrase in there where you were talking about

scratching, scraping, building up, tearing down, surviving. I thought those

words could have been applied to anybody trying to make it in Northern Ontario

in the early part of the last century.

MT

Oh yeah. I'm not

suggesting that my experience was unique. I think a lot of (people), certainly a lot of Jewish kids in particular,

were yearning for some kind of broader Jewish experience, which you couldn't

possibly get in a small town. So yes, we had to get out of the city. Our

parents even encouraged us to get out. I know very few parents in Sault Ste.

Marie who urged their children to stay there.

DBD

Most of your fans, of course, know that your life was dominated by a career in

corporate law. When you left it would have been to not necessarily pursue law,

but you would have gone to university down south, what was your first degree in?

MT

Originally, my father

was very anxious for me to be a doctor. As far as he was concerned, there was

only one profession in the world. And that was medicine. And he actually hated

lawyers. And we had quite a lot of tension between him and me over that

subject. So I went for one year to the University of Chicago and took some

science courses, but I was not happy with it at all. And I transferred to the

University of Toronto, and eventually got my own way. Well, actually a

compromise. I wanted to go into journalism, and I compromised with my father and

went into law, which he was not thrilled about although he accepted it

eventually

DBD

As preferable to a career in the nefarious world of journalism?

MT

Well, journalism, had a

funny reputation in Jewish life. On one hand, there were many great Jewish

journalists and writers, Isaac Bashevis Singer, at the time, was one of the

greatest and still is one of the greatest of all time. There were a number of

popular and excellent Jewish journalists and writers. But on the other hand,

old fashioned Eastern European Jews regarded literature as a third-rate kind of

profession because so many writers in Europe live from hand to mouth,

literally. And this is not what our parents wanted for us. They wanted the

security of a good old-fashioned profession like medicine, number one,

dentistry, number two, and maybe a lawyer if you couldn't be anything better.

DBD

Of course, you won the

Leacock medal. Could you describe the impact of the Leacock medal on (your career)?

MT

Well, I'll never forget,

I was sitting in my office, I guess it was in May of 1975, and Eve Orpen of

blessed memory called me. She was one of the publishers of Lester and Orpen.

And she said, “Morley, are you sitting down?” I still remember that line, “Morley,

are you sitting down?” I said, “Yes, I am. Why?” And she said, “You won the Leacock award.”

And it was a huge

thrill. It was the beginning of a long relationship that I have had with the

folks that are in Orillia, the Leacock people. A very long, rich, happy, lots

of fun kind of relationship over many, many years. It’s been a big part of our

lives, both Anna Pearl’s, my wife, and my life.

DBD

I know your son passed away tragically, some 10 years ago, and I hesitate to

ask, but I hope your wife is still with you?

MT

Oh, yes. She's sitting

across the table in the dining room as we speak.

DBD

That's wonderful.

MT

And now she's 91. Ninety-one going on 26.

Yes, we lost our son,

who was a lawyer who died of cancer. But fortunately, our daughter-in-law is

here and two wonderful grandchildren. One of them just got called to the bar.

And then our daughter is married to a television writer living in Santa Monica,

California, and they have two children, who are both university graduates and are

out in the world making a living.

So, we are very lucky.