But we will not. We want to run

forever in the scorching sun.”

Lin Yutang

Knowing that I

like to study the resident sense of humour when travelling, my friend Jane Tsai

said “definitely Lin Yu-tang would be the Chinese author that you are looking

for” after I told her I would be going to Taipei in the fall of 2017.

“When I was

growing up, he was the revered master of humour in China and Taiwan,” she said.

“You should have fun exploring his work.”

Jane pointed me

to two of Lin’s books: My Country My

People, an attempt to address some myths “Westerners” had about the Chinese,

and The Importance of Living, a book

that promoted the inherent rationality of human beings. Lin wrote both books in the

mid-1930s as those humans swirled toward the brutal irrationality of war.

A Window on Chinese Philosophies

Dr. Lin tried to build a porthole to Oriental mentality and, particularly, the thinkers of the past. Though a scholar with graduate degrees from Leipzig and Harvard, Lin eschewed the label of philosopher and presented himself instead as a humble purveyor of the thoughts of Confucius, Buddha, and others.

Dr. Lin tried to build a porthole to Oriental mentality and, particularly, the thinkers of the past. Though a scholar with graduate degrees from Leipzig and Harvard, Lin eschewed the label of philosopher and presented himself instead as a humble purveyor of the thoughts of Confucius, Buddha, and others.

“I

often study the joys and regrets of the ancient people,” he said. “As I lean

over their writings … (I) see that they were moved exactly as ourselves.”

“I

often study the joys and regrets of the ancient people,” he said. “As I lean

over their writings … (I) see that they were moved exactly as ourselves.”

Lin

tells his readers that respect for the wisdom of the past is a

feature of daily Chinese life. This

shows in the “the premium placed upon old age in China” where “it is

a privilege of the old people to talk, while the young must listen and hold

their tongue.”

Always wrapped in

an amiable case for tolerance, Lin’s books pull up many ideas

from the past that sparkle with a thoughtful kind of optimism.

“The

mature Chinese is always a person who refuses to think too hard or to believe

in any single idea or faith or school of philosophy whole-heartedly,” he

writes. “Only an insane type of mind can erect the state into a god and make of

it a fetish to swallow up the individual’s right of thinking, feeling and the

pursuit of happiness.”

In the early 21st

century, we might find solace in his suggestion that when a small man “casts a

long shadow,” it means the sun is about to set on him and in his hope that as

machines assume a bigger role in our world, we will be edging “nearer to the age of leisure,

and man will be compelled to play more.”

Taipei Tips on Humour Writing

Lin also spends a lot of time thinking about the craft of writing, and perhaps because he sought to speak to one culture from a footing in another and to give voice to ancient times today, he stressed the need to keep the perceptions of the audience in mind. He reminds us that writing and reading are acts “consisting of two sides, the author and the reader.”

Lin also spends a lot of time thinking about the craft of writing, and perhaps because he sought to speak to one culture from a footing in another and to give voice to ancient times today, he stressed the need to keep the perceptions of the audience in mind. He reminds us that writing and reading are acts “consisting of two sides, the author and the reader.”

But as the

“scorching sun” comment above suggests, the Professor couples his lessons on

writing and scholarly research with a case for finding time to just take it

easy, to slow down, to live “in harmony with the rhythm of nature,” and to contemplate

life with a smile. He argued that to

achieve brilliance, we need, like good wine, to sit still, let time pass, and

mellow. It occurred to me that this slowing

down and taking life in a light-hearted way advice might also be useful in any quest

to be a clear thinker and humorous writer.

Amused and

intrigued, I wanted to know more and searched for other quotes and biographical

material. I learned that though Lin was

born on the Mainland (1865) and died in Hong Kong (1976), he spent the last ten

years of his life in Taiwan. He designed

and built a house on the slopes of Yangminshan mountain just north of Taipei,

and his body lies entombed in the garden behind the home. Now known as “Lin

Yutang House,” it serves as a library, museum, and education centre open to

the public.

Lin and Leacock

If my trip to Taipei had not been short, work-related, and laden with meetings, I would have made plans to visit Lin Yu-tang House from the outset.

If my trip to Taipei had not been short, work-related, and laden with meetings, I would have made plans to visit Lin Yu-tang House from the outset.

But when I arrived

in Taipei, I learned that a visit to the House would mean walking several miles

up winding roads from the closest subway stop.

I couldn’t see how a visit to the

place could fit into my tight four-day schedule and tried to push the idea out

of my mind.

But this grew

harder and harder to do that evening as I read more of The Importance of Living and particularly

when I came upon sections that spoke directly to my interests in the Chinese sense of humour, mused on the

craft of humour writing, and, to my surprise - talked about Canadian humorist Stephen Leacock. Under the dark clouds of his

times, Lin suggests in The Importance of

Living that the world’s humorists might be the key to averting war and says

that Leacock, in particular, should be called upon to ensure peace.

“Send for instance, five or six of the world’s best humorists

to an international conference, and give them the plenipotentiary powers of

autocrats,” Lin says. “and the world will be saved.”

He puts Stephen Leacock in the chair of this imagined peace conference explaining

the Canadian humorist would win the world over with a general apology for the foibles

common to all of humanity, “gently reminding us that in the matter of stupidity

and sheer foolishness no nation can claim itself to be the superior of others.”

Lin admired other Western humorists as well. In their writings, he saw the means of tying

man’s dreams to the physical world saying while it is important to dream, it

was equally important to retain the capacity to laugh at those dreams and integrate

them with the realities of life.

Lin admired other Western humorists as well. In their writings, he saw the means of tying

man’s dreams to the physical world saying while it is important to dream, it

was equally important to retain the capacity to laugh at those dreams and integrate

them with the realities of life.

Lin did not immediately see a parallel in Chinese literature

and even undertook to create his own, original wording to translate the notion

of Western humour for the Chinese. Yet,

when describing Chinese culture and its ideal human manifestation, he cites “the

happy go lucky, carefree scamp,” and his views and insights on humour and

humour writing draw on Chinese philosophy as much as the literature of the West.

In reading these references, I realized that the tangled

lines and box-like symbols of Chinese writing make people laugh and feel not in

literal meanings but rather in the memories and images that those sounds and

words evoke. Recognizing this, Lin notes

that Chinese poets and scholars always gave

themselves evocative names, like – Tu Fu (“The Guest of Rivers and Lakes”) and

Su Tungp’o (“The Recluse of the Eastern Hillside”) and other names with

original meanings like the “Carefree Man of a Misty Lake” and “The Old Man of

the Haze-Girdled Tower.” Single Chinese

words can alone compel one to envisage multifaceted acts like walking out into a

courtyard after a full meal, staring at the sky, and waiting for the moon to

rise. Other words can evoke nuanced images

such as a man travelling the world in his imagination while lying in bed.

Knowing that the ancient Chinese poets had access to tools

like these, it becomes easier to understand how their work became so powerful

and enduring.

A Pilgrimage to the Humorist's Home

I loved the thinking, the style, and

soft wisdom of Lin’s books and decided I had to slip out of my meetings for a few hours and make a to

Lin Yutang House. With the help of a

volunteer translator and a fist of New Taiwanese dollars, I arranged with a cab

driver to take me up the mountain on the understanding that he would wait while

I made a heated tour of the property and home.

As our cab moved through Taipei, it became clear that neither

the driver nor the ambient traffic recognized the need to make this a quick

trip. Clogged streets in a big Asian city shouldn’t shock, but light rain and

slippery pavement slowed everyone a bit on this day, and my driver kept pulling

over in the midst of traffic, chatting in Mandarin and pointing out the sites. I grinned, nodded, and gently waved to keep

going. When he stopped on an overpass

and tried to get me to photograph the National Palace Museum, I grew a bit

tense, glared, and shook my head.

As we moved on and climbed the mountainside, rounded the wet curves,

and looked out on the city, I tried to forget my schedule and relax. Giant, colorful flowers filled the cab, maybe

there to offset the smell of smoke in the front and the sweaty tourists in the back, and I

pointed my nose toward the pleasant part of the air and thought about Lin

Yutang’s counsel.

Spotting his house as we approached, I pulled out my phone,

checked my watch, and plotted my hasty tour of the site. On this drizzly weekday afternoon in October,

only a few others were at the site and it took a while to find someone who

could sell me a ticket.

Coming back to the counter, I noticed that my cab had disappeared

and wondered exactly what the Chinese speaker back in Taipei had actually

said to the driver.

Coming back to the counter, I noticed that my cab had disappeared

and wondered exactly what the Chinese speaker back in Taipei had actually

said to the driver. Not sure when he would return and not wanting to run up the fare, I checked out the house as quickly as I could. The exhibitions do not consume a lot of floorspace. Arguably, the best part - Dr. Lin’s study - lies immediately to the right of the entrance. With crammed bookshelves, an old desk and padded chairs, it certainly feels like a philosopher’s thinking chamber. The other rooms display furniture and photos, paintings and sculptures, clothing and personal items. I took pictures with my phone, finished my tour in about fifteen minutes, and again looked out front hoping to see my taxi and wondering if the staff could call another.

The cab driver didn’t come back for another hour. During this time, I kept going around the

house again and again. I made three tours

of the rooms, checked out the café, and circled the exterior twice. Slowing

down a bit more each time, I always noticed something I had missed before, each time appreciating the experience and Lin Yutang a little more.

In his den, I noted the eclectic collection of books, most in

Chinese, which I assumed were poetry or philosophy for no other reason than

their aged appearance. The books in English were a mix of popular novels,

history, and academic works. I recognized manuscripts of Lin Yutang’s Chinese-English

Dictionary, and this seemed to exemplify his role as a bridge between two

worlds.

In the

other rooms, I realized that the paintings

and calligraphy were actually works done by Lin himself, and when I saw the

photos of his wife, I could feel the affection and warmth of life in this home.

The glass cases that at first seem an odd, haphazard assortment actually spoke

in a thematic way to that blend of thinking, doing, smiling, and relaxing expressed

in his books. The variety of pipes, for example, reminded me of Lin’s funny essay

on smoking and his tribute to its capacity to relax and induce reflection.

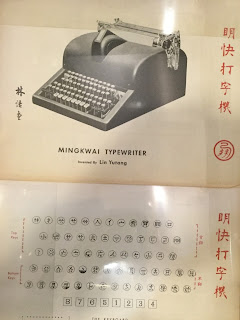

I knew that Dr. Lin had invented, built and sold a Chinese

typewriter, the first workable model some suggest, and I had noticed drawings

of the device when I first made my tour of the House. The second time I paused in front of the

display and absorbed that this was only one of a number of inventions and that

Lin was not merely a tinkerer who built a particular tool for his own trade,

but had a creative mind that dipped into many arena.

“Today human progress still consists very largely in chasing

after some form or other of lice that is bothering human society,” he said in

speaking generally of the process of invention.

I had checked out the courtyard with its waterfall when I

first arrived, but now I noticed how it affected the entire home and how most

rooms felt its calming influence. It reminded me of the home’s purposeful

design as an integrated feature of the natural world. Built in layers, it starts with the park-like

mountainside property rim, followed by the outer walls around the gardens, then

the main structure and its rooms, and finally the courtyard in the middle.

“This is the

house, in which there is a garden, in which there is a home, in which there are

trees, above which is the sky, in which is the moon,” as the Lin Yutang House publicity

states.

As I strolled around outside,

I noticed the tangle of tree roots and the random rock piles that seemed to

flow around the building and embrace it. The property slopes down at the back, and the author’s tomb sits in the

gardens below the rear balcony. It

gleams and stands out as a shiny badge in the midst of the green and reminds

you that there is something special here even though the rest of the home feels

humble, natural, and otherwise unadorned.

Standing at Lin’s grave for the second time, instead of looking

down, I turned to a break in the leafy trees that framed a view of the valley,

and immediately, I thought of Lin’s claim that the poorest man on a

mountainside lived a richer life than the wealthiest one in the city.

I knew he must have been looking at this view when he formed those thoughts.

I knew he must have been looking at this view when he formed those thoughts.

Coming back to the entrance, I saw my smiling cab driver waiting

by the entrance. I went over to him and

signaled that I wanted a little more time.

Inside once again, I peered into the only room I had not explored, initially

thinking it was an administrative office.

The narrow hall actually holds a reading room, space for lectures and

research, and a modest bookstore. I bought a few copies of My Country My

People and The Importance of Living as gifts for

people I like, and the young guy who

sold them to me offered to take my photo outside the house.

He told me to

stand in the sun for better light. I

did, but it didn’t feel quite right.

Heading back to

town and the blazing sun of meetings and work, I resolved to seek out the shade

once in a while, slow down a bit, and align a little with the rhythm of nature,

smiling and laughing more.

“For if this earthly existence is all we have, we must try the harder to enjoy it,” said Lin, a man who often waffled on the subject of religion and blind adherence to beliefs.

“For if this earthly existence is all we have, we must try the harder to enjoy it,” said Lin, a man who often waffled on the subject of religion and blind adherence to beliefs.

Out the cab

window rainwater bubbled in streams along the roadside, and I thought about

Lin’s ode to “Three laughs at the Tiger Brook,” a story represented by a famous

painting in Taipei’s National Palace Museum. The painting shows three religious

leaders laughing with the realization they had just passed into tiger territory

engrossed in conversation. Their unity in humour and the story came to

represent the ideal of harmony among Confucianism, Taoism, and Buddhism in

ancient China and is an enduring symbol of the potential for peaceful

co-existence with nature.

Out the cab

window rainwater bubbled in streams along the roadside, and I thought about

Lin’s ode to “Three laughs at the Tiger Brook,” a story represented by a famous

painting in Taipei’s National Palace Museum. The painting shows three religious

leaders laughing with the realization they had just passed into tiger territory

engrossed in conversation. Their unity in humour and the story came to

represent the ideal of harmony among Confucianism, Taoism, and Buddhism in

ancient China and is an enduring symbol of the potential for peaceful

co-existence with nature.

This time as we

went onto the highway overpass by the National Museum, I asked the driver to

slow down and pull over, and I took a photo.

October 2017