Be careful how you judge

a sixty-eight-year-old book

a sixty-eight-year-old book

The two-storey, nineteenth-century

manor sits in a leafy, established part of Peterborough. I’m glad that I didn’t

know about the house before I entered it. Learning within its walls convinced

me that I was on to something.

“He used to live here; in fact, I

bought the house from him,” my host said in reference to a famous former

inhabitant.

The cordial speaker, Professor Tom

Symons, shared this morsel and some funny stories as we discussed my interest

in the Leacock Medal books. Symons and his wife, Christine, had invited me to

their home for lemon cake and a cup of tea. My wife and I made the trip from

Ottawa in early 2013 not to see the house, not to hear about its past, and not

to eat. Michèle came along because she likes road trips, and I came to learn

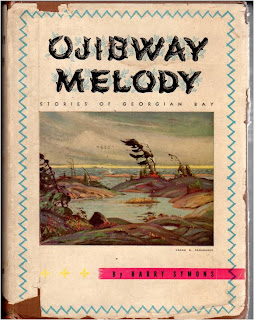

more about Tom’s father, Harry Lutz Symons, the author of Ojibway Melody: Stories of Georgian Bay, the 1947 Leacock Medal

book. Little has been published about Harry, and I wanted access to the family

archives at Trent University.

All I knew for sure about Harry Symons

was that he loved his cottage near Pointe-au-Baril on Georgian Bay and saw it

as his sanctuary.[1]

With Ojibway Melody, he tried to share

it, guiding us around the islands, pointing out the good fishing spots, and

describing the locals. The book can leave you with the feel of a warm

handshake, a pat on the back, and a canoe ride on sparkling waters.

Given Stephen Leacock’s association

with Ontario cottage country, the 1947 medal judges probably felt that this

book made a fitting first winner of the award established in Leacock’s honour.

Yet it struck me, initially, as a puzzle.

The writing seems like stream of

consciousness, nothing like the one-liners, jokes, or comic stories that we

consume as humour today. Ojibway

Melody[2]

merrily pours out a medley: hunting trips; the legend of Turtle Rock; the

whisky barrel that gave Pointe-au-Baril its name; the crow “Black Lucy”; the

rookery of lake birds; and Regatta Day, “with all its fun, and laughter, and

excitement, and crowds, and ice cream, and pop, and noise.”

At times, the book reads like a

transcription of musings over events just as they unfolded, like this

unedited bit of narration: “. . . for a while. But hold on a moment.

Perhaps that was . . . it might just

possibly have been . . . well YOU know . . .”

Harry Symons shifts the verb tense and

the perspective of the narrator regularly.[3] The

only consistency comes from his affection for “the local focal”: boats and

fishing. Canoes, inboards, outboards, and row boats. Pike, lunge and bass.

Early in the book, you might think Symons wrote it to celebrate the Ojibway

Hotel.[4]

But then he talks of the hotel with caution, saying he did not lust for places

where “ties and collars” were the norm. Harry says that if such a lifestyle

ever takes over Georgian Bay, the area will have “lost its savour and . . . the

ageless rocks will arise in all their dignity and crumble into dust.”

When I read this passage, I started to

understand. It sounded like something I had heard others say when I was young

and was the kind of thing my own father would have thought. I began to regard

Harry Symons as my own dad counselling me raconteur-style to slow down and

lighten up a bit.

Harry praised simple pleasures: “First

we swing our feet out of bed, and dangle them over the side, and keep our toes

off the floor just in case it is cold. Then we yawn a good deal and grumble,

and flex our arms, and wish we were back in bed . . . And quite often we just

do give up and crawl back in again . . .”

|

strains of careers, family, and a changing society. In the 1940s, Canadians also wanted to think about things other than war. Ojibway Melody, though written in 1944 and 1945, met that need. It only mentions the World War II context in a vague reference to “the labour shortage in wartime.” The incongruity of this book exists, not in the text alone, but between its dark background and cheery content.

Harry Symons[5]

had special reason to block out the violence and seek refuge in the boats

and fishing around Georgian Bay.

Born in Toronto in 1893, Harry loved

physical exertion and the outdoors. He even quarterbacked for the Toronto

Argonauts, served as captain of a varsity football team, and sailed

competitively. He spent summers on a survey crew, camping and hiking through

the wilderness around Georgian Bay. The beauty of the forests and the waters

fixed in his head and would turn out to be important to his psyche and

survival.

When World War I broke out in 1914,

Harry Symons left school and joined the army to serve on the front lines in

Europe, where his mind clenched onto images of the islands around the Bay. In

August 1916, he transferred to the Royal Flying Corps and the cockpit of a

Sopwith Camel. Harry survived, scoring enough kills to place him in the “Ace”

category. Yet he never talked much about the war, and after his death in 1961,

aviation historians described his exploits as “unknown to all but the most

diligent researchers.”[6]

The future Leacock medallist did not

consider the wartime heroics nearly as important as his post-plane-crash stay

in an English hospital. That’s where he met a nurse named Dorothy.[7]

After he returned to Canada with Dorothy at his side, he bought the

Georgian Bay cottage “Yoctangee,” put the war behind him, pursued a career in

real estate and insurance, and started a family that would eventually include

Tom and seven other children.

Tom Symons[8] had

talked to me on the phone and had sent me some records as well as having

invited me to his Peterborough home, which I learned, only after taking off my

boots and sitting down, carries formal designation as Marchbanks House, a

historic site and former home of novelist Robertson Davies. Davies wrote his

Leacock Medal-winning novel in this house. W.O. Mitchell and others also

honoured by the Leacock prize regularly visited the place and sat in the chair

that held my butt that early 2013 afternoon. Tom, who also showed me the artist’s

cast for the first Leacock Medal,[9]

told me all this to encourage me in my project. He wanted, in particular,

to share the story of his dad’s book Ojibway

Melody and the impact it has had on the academic study of Canada.

“The book ... means a great deal to

me. I often think of it because it gives me answers when I am considering

things--it helps as a compass when I have difficult chores from time to time,”

said Tom Symons. “First of all, it reads the way my father talked, and I enjoy

that. I can hear his voice, but I also hear his respect and his concern for

others. The book is all about it--between the lines sometimes.”

He was touched, in particular, by his

father’s empathy for the Ojibway people.

“That chapter is superb,” said the

author’s son, now well into his eighties. “I was raised with that concern, and

I am sure that that is one of the reasons Trent was the first university in

Canada to have a department of Native studies.”

Tom Symons, the first president of

that university and a founder of the field of Canadian Studies, served as chair

of the 1970s national commission on the subject of Canada.[10] The

commission’s 1976 report, To Know

Ourselves,[11]

set out the road map for the subsequent study of Canada and the promotion

of Canadians as a people that mix sensitivity with conviction, qualities that

Symons saw in his dad’s book Ojibway

Melody.

“My interest in the rapport between

French and English people is drawn from the book,” said Tom. “You sometimes don’t

recognize the deeper values of the author because it is written so amiably, but

the book is a touchstone for me and the things I value.”

This conversation convinced me that

every Canadian could benefit from a trip to the cottage described in the first

Leacock Medal-winning book and, again, made me think that I might be on to

something with this project.

It also gave me hope that a person

who, like Ojibway Melody, is over

sixty years old and a little tattered on the edges might still have something

worthwhile to say about Canadian humour.

>>>

Writing Exercise

In the voice of a

former fishing guide from Georgian Bay, describe your first day at work as a

stockbroker on Bay Street in 1987.

[1] Harry Symons was a vice-president with

Confederation Life in charge of real estate holdings in Toronto and liked to

get away from the pressures of the city.

[2] Symons held the full copyright on the book. The

first edition of Ojibway Melody carried the marks of Copp Clark Co. and

Ambassador Books; the former did the printing and the latter was Harry’s distributor.

[3] He uses the third person perspective in the

first and last chapters (“The Advance Party” and “The Rearguard”) and more

often the royal first person plural (“we rocked on our toes”) after initiating

his story with “I.”

[4] The landmark Ojibway Hotel endures to this day

in the form of a clubhouse and community centre.

[5] Personal papers that include the original typed

manuscript of Ojibway Melody can

be accessed with prior permission at Trent University Archives, Trent University,

Peterborough, Ontario, Thomas H.B. Symons Fonds, 1929–99 Accession number 01–003 (box 4 folder 6).

[6] H. Creagen, “H.L. Symons--Ace & Author,”

Canadian Aviation Historical Society Journal, Vol. 2, No. 4 (Winter 1964), 113.

[7] The convalescent hospital was established by

Harry’s future father-in-law, the wealthy Canadian lawyer and businessman

William Perkins Bull. Other patients at the centre during this period included

decorated pilot Billy Bishop and future Governor General Georges Vanier.

[8] For more on Harry’s

son, see Ralph Heintzman, ed., Tom Symons: A Canadian Life (Ottawa:

University of Ottawa Press, 2011), which featured contributions from many

Canadian politicians, writers, and scholars.

[9] Harry Symons’s family has possession of

sculptor Emanuel Hahn’s original casts of Stephen Leacock’s face in profile and

the Sunshine and Mosquito back used to mint the Leacock medals.

[10] Tom Symons, born May 30, 1929, also served as chair

of the Ontario Heritage Trust, the Ontario Human Rights Commission, and the

Historic Sites and Monuments Board.

[11] The history of Canadian Studies and the

Commission are outlined in the Canadian Encyclopedia (online)--Canadian Studies--author

S. McMullin http://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.com/articles/canadian-studies accessed September 28, 2013.