Lesson 5

Finding your own “moveable feast”

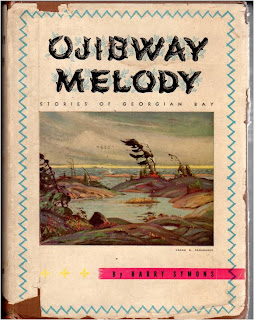

***Graphic 010 (book cover)

As a teen in 1960s

Ontario, I fantasized that some heavenly intervention might allow me to pass

high school French so I could go off to Paris and hang out with someone who

might be named Collette, Michèle, or something like that. Ernest Hemingway’s

death, image, and aftermath loomed large in pop culture and in young male minds

at that time.

He told us, “If you’re lucky enough to

have lived in Paris as a young man, then wherever you go for the rest of your

life, it stays with you,” adding that celebrated comment: “for Paris is a

moveable feast.”[1]

Paris was not in the cards for me.

Instead, I moved to Vancouver, where I had relatives, a place at Simon Fraser

University, and my own experiences. They eventually led me to meet writer Eric

Nicol and to spend an afternoon at his Point Grey home.[2] For

these and other reasons, Nicol’s book The

Roving I, the first of three to win the Leacock Medal for him, mixed Paris

and Vancouver together in my mind.

In this 1951 medal winner, Nicol tells

of ordinary things: a visit to the library, a ride on a train, and a walk

through city streets. There’s not much interaction with other people. Yet the

book holds your interest because those streets run through Paris, and the train

takes you across the French countryside. Nicol wrote the book during his time

as a graduate student at the Sorbonne in the late 1940s. He assembled The Roving I as a travel narrative aimed

at a Canadian audience, drawing it from the columns that helped pay his

expenses in the City of Light. Eric Nicol’s later books also repackaged

newspaper columns, but those collections often lacked any unifying theme. The Roving I had the story-like

framework of his year in Paris, and this makes it an easier read.

***Graphic 011 (author)

Thousands of Canadians around Nicol’s

age had seen Europe the hard way a few years earlier; Nicol, however, passed

his military service in Ottawa offices, and having been “spared the

hostilities,” he could ride on the postwar wave that regarded Paris with a

smile. Nicol, with his master’s degree in French literature from UBC, had

genuine affection for Parisian life, and this shows, too.

The tone of the book and many of its

observations may seem quaint in an Internet world. Yet some passages could have

been written yesterday, and pretty much all of it remains funny. This is

because Nicol describes the walks through the streets of the everyday with

weird words and silly detail--as he did on his day at the bibliothèque: “A little man saved from midgetdom only by his

bowler. With hands resting on his behind, he fluffs out the wings of his

swallowtail coat (circa 1885), like a nervous blowfly.”[3]

Nicol’s inclination to elaborate on the

ordinary while skating over the elaborate sparkles in his description of a side

trip to Florence. In it, he devotes two and a half pages to the process of

eating spaghetti and only a paragraph to the Uffizi. He not only elevates

mundane events with his descriptions, but manages to generate stories of things

that never happened--like an imagined date with a woman who might have been

named “Collette,” had she shown up. Nicol never fully explains the decision to

leave the Sorbonne before completing his doctorate, but he felt lonely. He laments

not having someone with whom to share his Paris experience.

What Hemingway meant by “moveable

feast,” of course, was that the 1920s Paris of artists, writers, and poets was

his personal foundation: the learning, the relationships, and the experiences

that he would feed upon for the rest of his life. Nicol, at the age of thirty,

had passed out of the young-man stage (his Collette imaginings notwithstanding)

when he attended university in Paris. As a published author and veteran

journalist, he had already found his comic voice and decided that British

Columbia would be his touchstone.

This meant that Nicol brought his own

moveable feast[4]

to Paris and to the book that allowed him to share those Sorbonne days with

thousands of Canadians, including one living in Ottawa who still feasts on

young-man thoughts of Vancouver from time to time.

Writing Exercise

In a paragraph,

explain why Sudbury, Ontario, is your “moveable feast.”

[1] The quote, attributed to Hemingway by his

biographer, A.E. Hotchner, and slapped on the cover of a post-suicide

collection, now strikes me as too cute or rehearsed to be authentic

conversation, but the connotation makes sense.

[2] I interviewed him for Vancouver radio station

CJVB in 1978. Nicol (1919–2011) lived in that same house from 1957 to the end

of his life.

[3] This excerpt was also highlighted by

Michael Nolan in “Eric Nicol,” in Dictionary

of Literary Biography, vol. 362, Canadian Literary Humorists, ed.

Paul Matthew St. Pierre (Detroit: Gale, 2011). Anyone interested in substantive

bios of humour writers should access the St. Pierre collection.

[4] On the subject of

moveable feasts, the ever-modest Nicol said, “In the

feast of life, I have been a digestive biscuit.” Allen Twigg, “Tribute

to Eric Nicol,” BC Bookworld, Spring

2011, 17–18.